The news used to be driven by the truth, at least in theory. Today — more than ever — it’s driven by story (as Trump knows well), which requires sources of contradiction. When contradiction is in short supply, Twitter conveniently provides it. USA Today knows this at a deep and instinctive level. They continue to blaze the path into The Age of Mediocrity.

STORY TRUMPS TRUTH today in ways not seen since the medieval Dark Ages. Brought to you by science, technology and Twitter, run amok.

STORY TRUMPS TRUTH

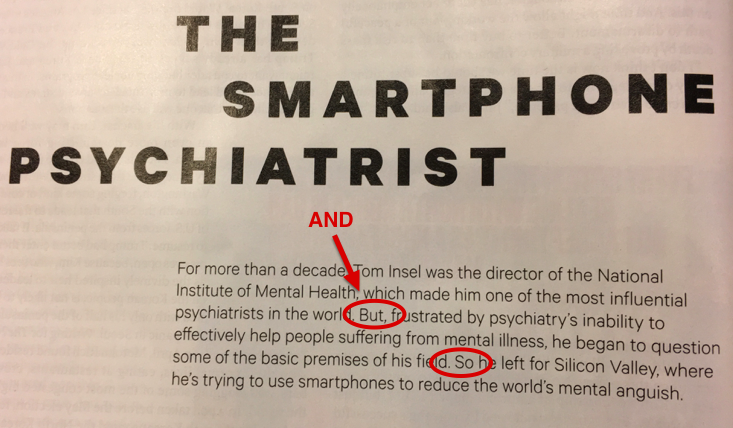

Narrative consists of three forces — AGREEMENT, CONTRADICTION, CONSEQUENCE. If you want a solid narrative structure, you need sources of all three.

Furthermore, Rule #1 of storytelling is that “The power of storytelling rests in the specifics.”

Today’s news media has a ravenous appetite for both contradiction and specifics. Twitter provides both.

If I tell you Ann Coulter got into a spat on a flight, that’s moderately interesting. But if I can use Twitter to quote specific words from her AND specific words of opposition, as USA Today does in this article today, it’s much more powerful. Who cares whether the Twitter sources are reputable.

Even more to the point, if I tell you Ed Sheeran’s appearance on “Game of Thrones” sucked, that’s moderately interesting. But it’s much more interesting and engaging if I can cite specific voices — regardless of whether they are professional movie critics. Who cares who they are, they are sources of contradiction and specifics — precious narrative fuel.

It’s happening all day, every day now. How do movie critics even have a job any more? How do any experts have jobs? We are devolving into a gelatinous mass of supposedly all-knowing crowd-sourced knowledge, driven by an increasingly insatiable thirst for narrative, accompanied by an increasing disgust and even contempt for what used to be known as “the truth.”

Thus continues our information-glutted sleigh ride into The Age of Mediocrity, overseen by The Master of Contradiction in the White House. And followed suit by the increasingly dull and mediocre Democrats who respect and value the voices of mediocrity.