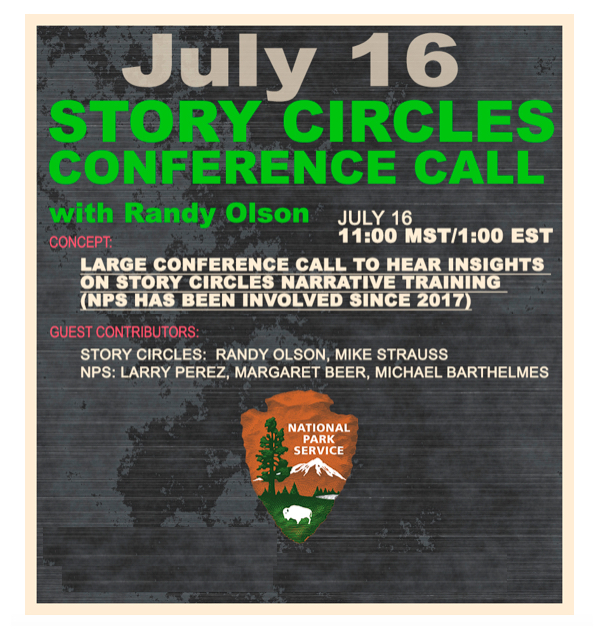

Yesterday, to enjoy 90 minutes of escapism, we ran a Story Circles “Demo Session” with 5 of our recent graduates. It was fun, interesting, and a valuable thing to do in a time where the communication of science has never, ever been more important. You can listen to the audio of the session here, and “play along” using the four abstracts and one narrative below to get a feel for how the training works.

STARS OF THE SHOW: Clockwise from top left: Michael Bart (National Park Service, Colorado), Andrea Taylor (School of Psychology, University of Waikato, NZ), Alison Mims (National Park Service, Colorado), Randy Olson (scientist-turned-filmmaker), Mevagh Sanson (School of Psychology, University of Waikato, NZ), Elizabeth Stulberg (Agronomy, Crops, and Soil Science Societies).

THE STANDARD ONE HOUR STORY CIRCLES SESSION

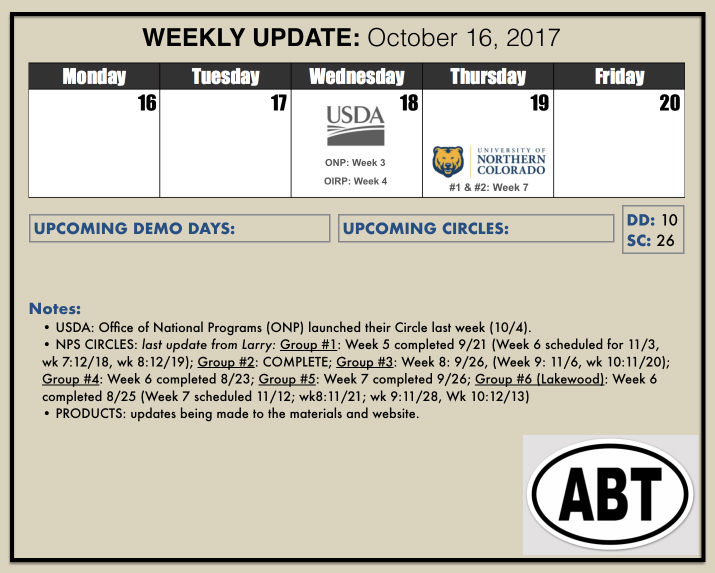

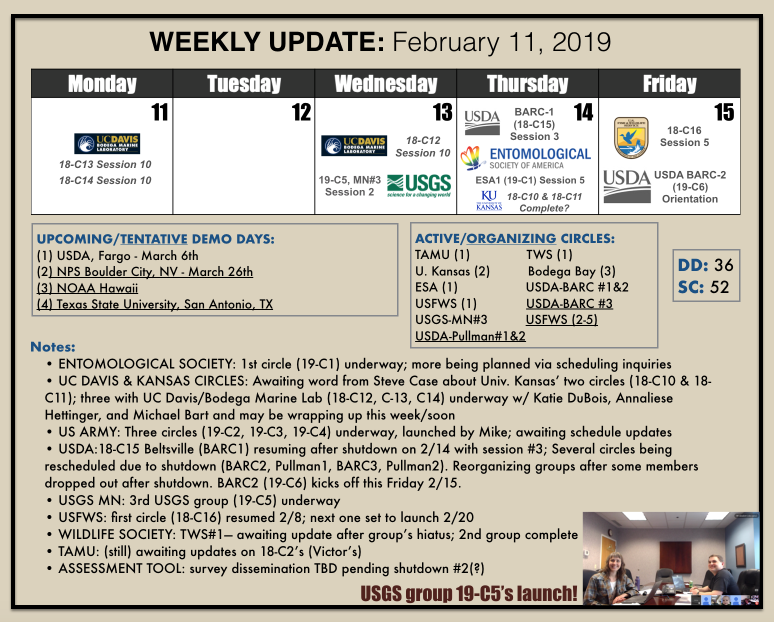

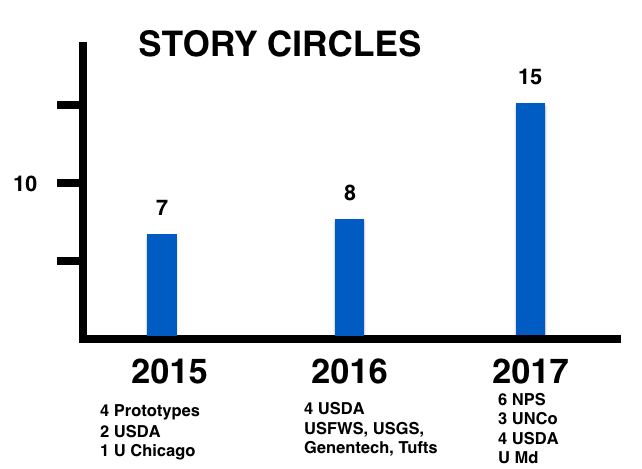

Story Circles Narrative Training consists of 10 one hour sessions of five people meeting, usually once a week. The goal of the training is to strengthen your “narrative intuition” — a term I coined in my 2015 book, “Houston, We Have A Narrative,” which provides background on all of the concepts presented in the training.

The first half hour is Narrative Analysis where they are given 5 texts to analyze using the ABT Framework (for this demo session we only used four). The second half of the hour is Narrative Development where each participant has an assignment. For this session the assignment were as follows and the materials analyzed are below.

MODERATOR – Michael

NARRATIVE – Mevagh

WORD TEMPLATE /ARGUMENT – Andrea

SENTENCE TEMPLATE – Elizabeth

PARAGRAPH TEMPLATE – Alison

NARRATIVE ANALYSIS

Abstract 1

Neuron:glial ratios were determined in specific regions of Albert Einstein’s cerebral cortex to compare with samples from 11 human male cortices. Cell counts were made on either 6- or 20-μm sections from areas 9 and 39 from each hemisphere. All sections were stained with the Klüver-Barrera stain to differentiate neurons from glia, both astrocytes and oliogdendrocytes. Cell counts were made under oil immersion from the crown of the gyrus to the white matter by following a red line drawn on the coverslip. The average number of neurons and glial cells was determined per microscopic field. The results of the analysis suggest that in left area 39, the neuronal:glial ratio for the Einstein brain is significantly smaller than the mean for the control population (t = 2.62, df 9, p < 0.05, two-tailed). Einstein’s brain did not differ significantly in the neuronal:glial ratio from the controls in any of the other three areas studied.

Abstract 2

Tumor cells can spread to distant sites through their ability to switch between mesenchymal and amoeboid (bleb-based) migration. Because of this difference, inhibitors of metastasis must account for each migration mode. However, the role of Vimentin in amoeboid migration has not been determined. Since amoeboid, Leader Bleb-Based Migration (LBBM) occurs in confined spaces and Vimentin is known to strongly influence cell mechanical properties, we hypothesized that a flexible Vimentin network is required for fast amoeboid migration. Tothisend,here we determined the precise role of the Vimentin intermediate filament system in regulating the migration of amoeboid human cancer cells. Vimentin is a classic marker of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and is therefore an ideal target for a metastasis inhibitor. Using a previously developed PDMS slab-based approach to confine cells, RNAi-based Vimentin silencing, Vimentin over-expression, pharmacological treatments, and measurements of cell stiffness, we found that RNAi-mediated depletion of Vimentin increases LBBM by ~50% compared with control cells and that Vimentin over-expression and Simvastatin-induced Vimentin bundling inhibit fast amoeboid migration and proliferation. Importantly, these effects were independent of changes in actomyosin contractility. Our results indicate that a flexible Vimentin intermediate filament network promotes LBBM of amoeboid cancer cells in confined environments and that Vimentin bundling perturbs cell mechanical properties and thereby inhibits the invasive properties of cancer cells.

Abstract 3

Thirteen-year-old Kayla hosts a YouTube series called “Kayla’s Korner” where she gives advice to an imagined audience of her peers. She picks topics like “Being Yourself” and “Putting Yourself Out There” and stumbles her way through a pep-talk peppered with “like” and glances at her notes. A glimpse of the subscriber count shows that Kayla’s Korner hasn’t exactly taken off. Kayla airbrushes out her acne, and swoops on heavy eyeliner. This is a young girl trying to understand what she is going through, and she does so by positioning herself as an expert and a helper to others.

Abstract 4

Four male friends who live an ordinary existence in Kentucky come up with a scheme to make their lives more interesting. After a visit to Transylvania University, they concoct the idea to steal the rarest and most valuable books from the school’s library. As one of the most audacious art heists in U.S. history starts to unfold, the men question whether their attempts to inject excitement and purpose into their lives are simply misguided attempts at achieving the American dream.

NARRATIVE DEVELOPMENT

This is the narrative from Mevagh Sanson (a brief description of her dissertation research) that is the focus of the second half hour of the session.

Narrative:

We can be mentally whisked away from the present, back to re-live our past, or forward to “pre-live” our hypothetical future. Re-living our negative past too intensely and frequently can impair us in the present, as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. But PTSD is conceptualised only as a disorder in which people are haunted by their past. Given that re-living and pre-living are closely related abilities, I propose that pre-living our hypothetical negative future too intensely and frequently similarly impairs us, as “pre-traumatic stress disorder.” I will investigate the ways in which people are haunted by their future.