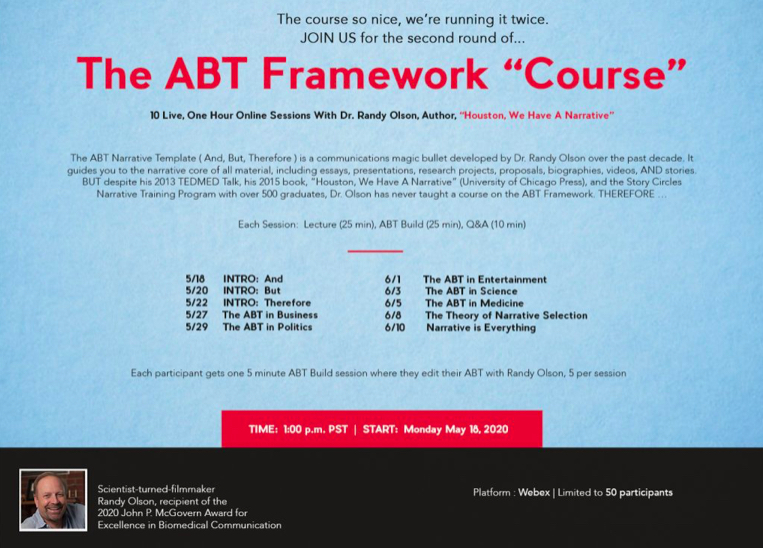

Want to climb into the ABT sandbox and build some narrative sand castles? We’re about to do it in a big way, for the first time ever, starting next Monday, April 20. This will be an online “course” but I say the word in quotes because it’s going to be so PARTICIPATORY. And fun. Here’s the details. You can ENROLL HERE — it’s open to everyone — and I do mean EVERYONE. It’s cheap and I sincerely promise, it will expand your mind.

TIME TO BUILD SOME NARRATIVE SAND CASTLES!

DESPERATE TIMES CALL FOR DESPERATE MEASURES

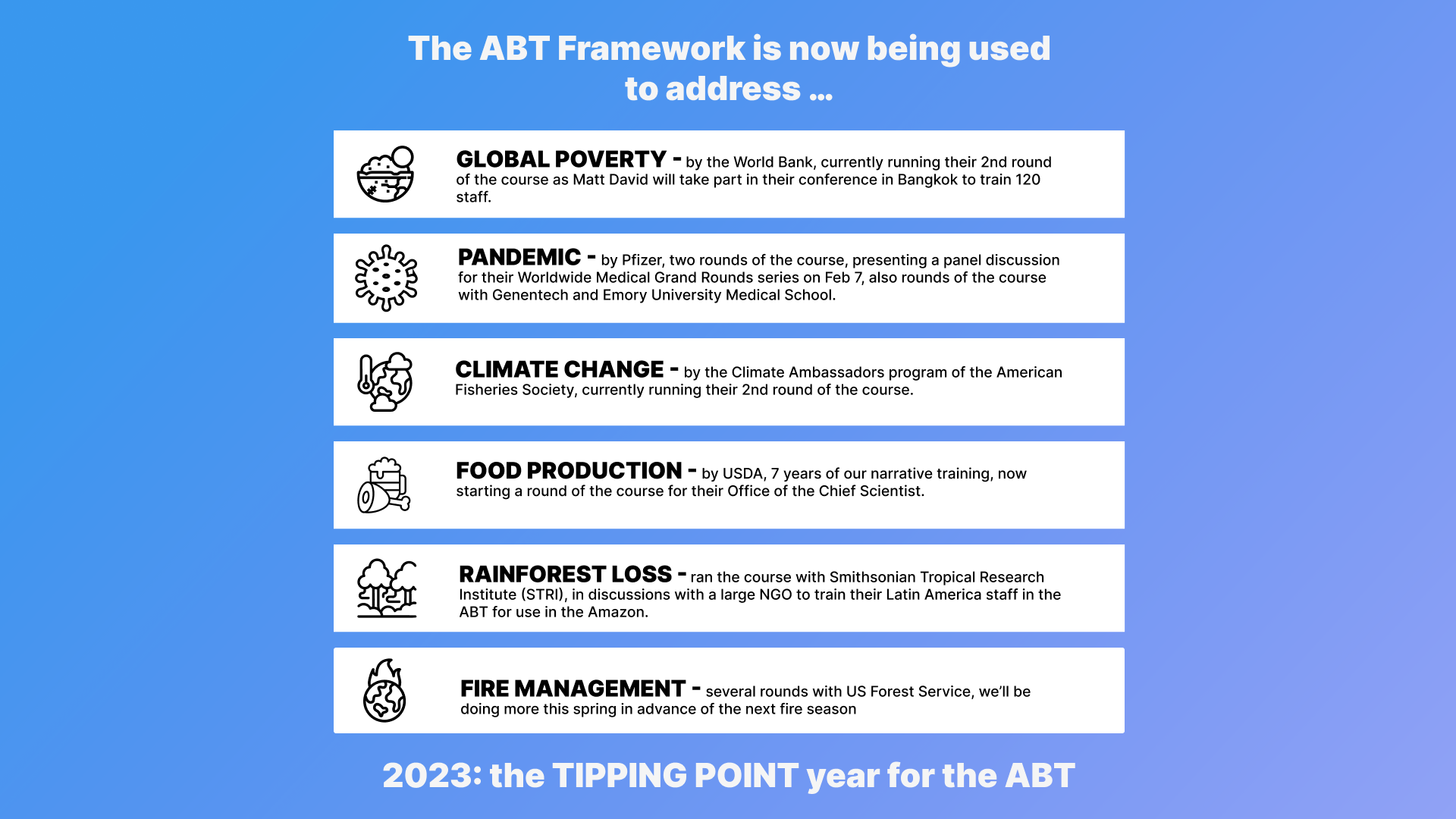

We’ve had a wonderful run with Story Circles Narrative Training 1.0 over the past 5 years. We’ve completed roughly 100 circles of 5 (or more occasionally) individuals each, producing over 500 graduates. The proof of how powerful and effective it has been is visible in the results of our Survey of Graduates last year.

Now it’s time to “advance the narrative.”

It’s also time for a little synthesis. I started assembling what we’ve learned last year with the book, “Narrative Is Everything.” Now we’re all stuck at home, so why not have some fun sharing the knowledge.

DON’T CALL IT A “COURSE”

This is going to be something more than just a “course.” It’s going to be a participatory journey. And not just for the participants, but for me, as well.

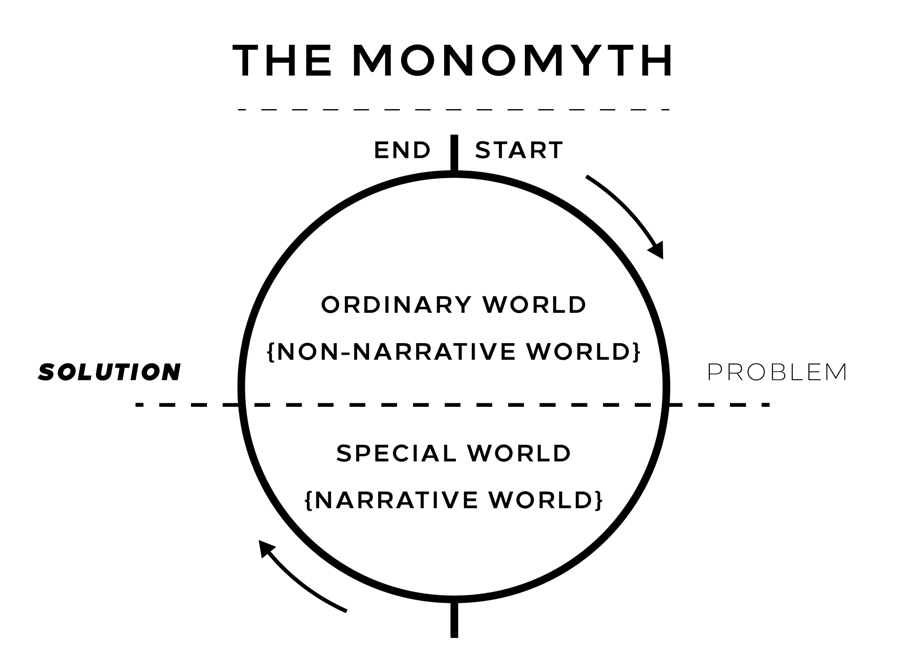

I formulated the ABT Narrative Template in 2012, gave a TEDMED Talk about it in 2013, laid it out in detail in my book, “Houston, We Have A Narrative,” in 2015, then began implementing it with our Story Circles Narrative Training program ever since.

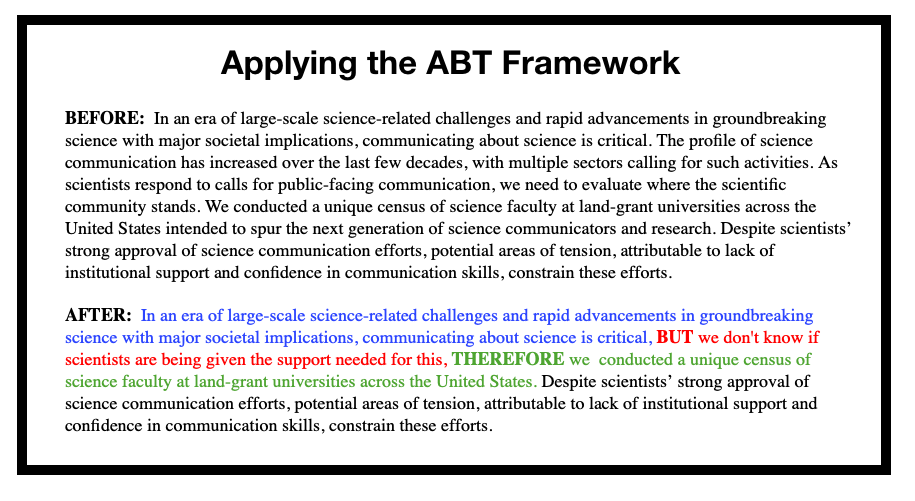

The whole concept is still a work in progress, as the participants in this “course” type thing will realize. There are no textbooks (yet) on the ABT Framework, but at this point, there are countless people putting it to work in trying to figure out the narrative core of their work, which means the AND (the context), the BUT (the problem being addressed), and the THEREFORE (what needs to be done).

There is so much to the ABT Framework that it’s definitely time to pull it all together into a “course” that in part is an argument along these lines: The ABT is a powerful communications tool AND lots of people are beginning to see how ubiquitous it is in our culture, BUT I’m going to argue even further — that it is everything, THEREFORE … I hope you’ll join us and hold my feet to the fire because … I might be wrong.

WHAT WE’LL BE TALKING ABOUT …

Each hour session will begin with a 25 minute lecture, followed by 25 minutes of my working with 5 individuals LIVE on their ABTs as the rest of the group listens in and offers up comments and questions in the CHAT BOX. At the end I’ll address a few of the questions in the 10 minutes of Q&A, but then later (probably that afternoon) I’ll also address other comments and questions from the Chat Box in writing, in an online forum we’ll be maintaining along with the “course.”

Here’s a little bit of teaser material for what each of the lectures will be about.

1 INTRO: AND (Agreement)

Seriously? An entire 25 minutes just for the one word, “AND”? Yes, starting with the 2015 study from the Stanford Literary Lab that documented the frequency of the use of this one seemingly meaningless word in the legendarily boring annual reports of the World Bank. Sadly, it’s a word with a big future, if we don’t realize how boring it is. And … tune in to hear lots more, about this, the most common word of agreement.

2 INTRO: BUT (Contradiction)

Is there a more important word in the entire English language? You might think so, BUT … I would argue not. The word “BUT” is the most common word of contradiction, and contradiction is at the center of narrative structure. AND … narrative structure goes back thousands of years — it’s how we communicate. I’ve got hours to say about this one word, BUT …

3 INTRO: THEREFORE (Consequence)

This is the real meat of what you’re here to hear. By the end of the first week of the course, everyone is going to want an answer to the basic question of, “So what’s the THEREFORE of this course?” It’s basically the old, “Where’s the beef?” question. And it turns out to be the real substance of the ABT — basically, enough with the A and the B, we want to know the T. THEREFORE, what are we going to learn with this course?

4 The ABT in Business

Business is branding, and branding is ABT. Yes, it’s that simple. It’s what makes your product sell. “Lots of companies make widgets that do this AND this, BUT nobody makes a widget that does this, THEREFORE, you need to buy my widget.” Yes, there’s a million more facets to the elusive art of branding, but at the core, it’s as simple as ABT because business is argument, and argument is ABT.

5 The ABT in Politics

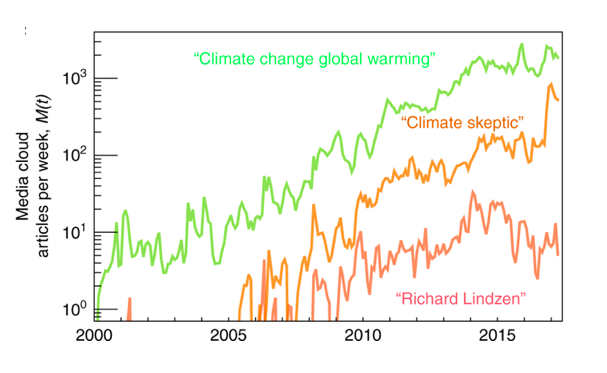

From the iconic Gettysburg Address onward, where you find great speeches, you’ll find the ABT at work. Narrative is leadership. People don’t follow leaders who are boring or confusing. From MLK, Jr to Richard Nixon’s megalomaniacal first inauguration address, every great speech is built around the ABT elements. In this lecture we’ll use the Narrative Index (the BUT/AND ratio) to reveal this.

6 The ABT in Entertainment

This is where it started. Aristotle and the Greeks first recognized the 5 part (which was essentially 3 part) structure of their plays. The rest … as they say … is … you guessed it — history. From Joseph Campbell to George Lucas to Oprah Winfrey delivering a Golden Globes speech for the ages. We live in a media society. Media is ABT. Today, narrative intuition is obligatory for success in all facets of life.

7 The ABT in Science

A century ago scientists “got it” on the ABT. They came together and established a structure for their communication that came to be known as the IMRAD Template (standing for Introduction, Methods, Results, And, Discussion). Today … a lot of that collective consciousness of narrative intuition has been lost in our information drenched sea of obfuscation. Guess what the result is for the communication of science in today’s world (not good).

8 The ABT in Medicine

For a teaser of this lecture read my article in Scientific American last month titled, “A New Tool for Humanizing Medicine: It’s called the ABT Template, and if you want to talk to patients simply and clearly, it’s ideal.”

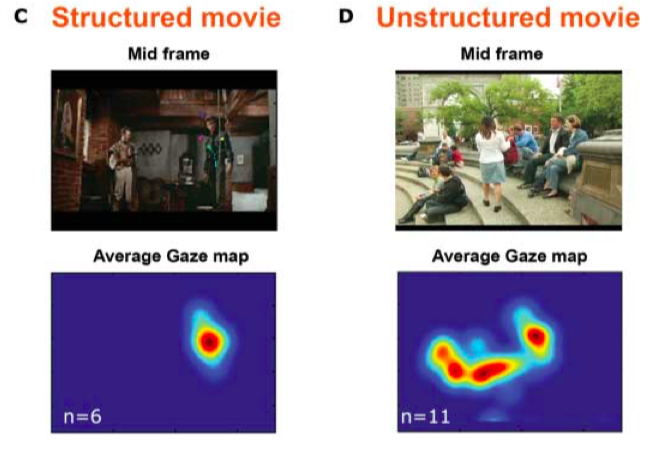

9 Narrative Selection

It’s a big concept, but by the time I get here, you’ll hopefully be right there with me in the realization that this is the most important shaping force of our entire culture. The brain is narrative. The brain selects what persists. Our culture is made up of what has persisted. Narrative is our culture.

10 Narrative is Everything

In the end, it’s not about the ABT. It’s about the three forces that underlie the three words — Agreement, Contradiction, Consequence. These are the forces you see at work in all communication. They are the elements that ultimately determine whether humans compete or cooperate. They are everything.

AND … THE PARTICIPATORY PART

The “course” will be limited to 50 participants because that’s the maximum number of 5 minute time slots we can fit. When you enroll, you have to submit your one sentence ABT (a one sentence statement using the words And, But, Therefore that is the narrative core of a project you’re working on).

For each session, 5 individuals will be chosen for the “ABT Build” part which will be 25 minutes in length. For each person, they will join me on screen to read their ABT once or twice or more, then I’ll start to work, dissecting it, using the set of tools we’ve developed in Story Circles to poke, probe, revise and hopefully ultimately strengthen it.

All the while, the rest of the group will be listening in, adding comments, questions and suggestions to the Chat Box. Eventually everyone will get their 5 minute session, which is always fun.

LAST NOTE: SORRY, THE SESSIONS WON’T BE RECORDED

Yeah. Bummer. I know. You were hoping you could sign up, go for a walk during the time slot, then listen to the session that evening. Not gonna happen. You miss it, you miss it.

I want all participants present for every session. Even if there’s only ten people who enroll, it’s going to be about EVERYONE taking part — listening, thinking, contributing.

And all “of the moment.” Experiential. You’ll want to be listening with every neuron in the narrative part of your brain, and then some.