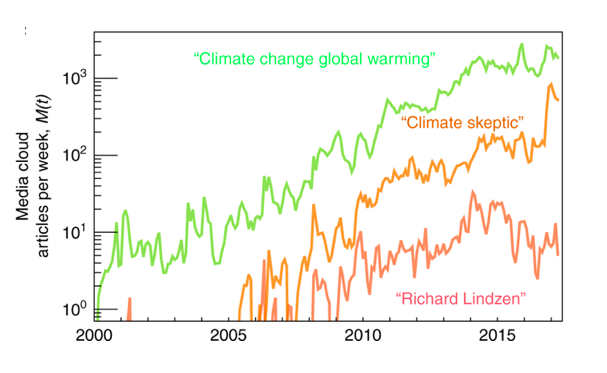

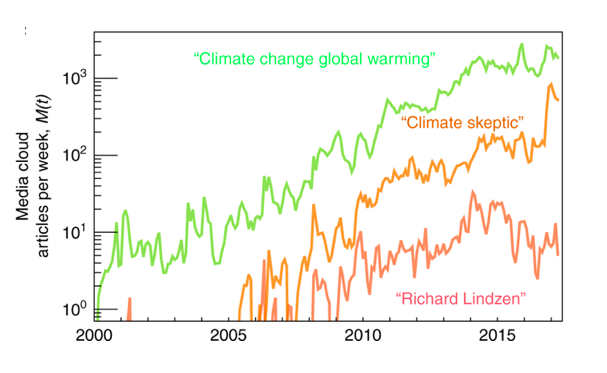

A new paper in Nature (that’s characterized by the standard obfuscation-rich academic style) seems mystified by how climate contrarians can get so much of the public’s attention when they are so few in numbers. The authors don’t seem to understand the difference between data and narrative, much less know how to consider “narrative strength.” Yes, in the world of data, it looks out of balance. But in the world of narrative — where a single anecdote out-weighs a massive sample size — it makes total sense. This is what should be called “Narrative Equivalence.” Nothing false about it to the average, non-intellectual. The challenge is for intellectuals to grasp this.

CLIMATE ENEMY #1. Marc Morano is the most prolific voice of climate skepticism, by far. His total publications are 35% more than his closest competitor.

A WORLD OF NOISE. Climate skeptics sure do know how to make noise.

MISTAKEN EQUIVALENCE

For about 15 years I’ve listened to bloggers complain about “false equivalence” when it comes to climate reporting. In articles like this they bemoan the idea that 97 percent of scientists agree on climate, yet so many articles present the two perspectives as if they were equal in validity. This is what they call “a false equivalency.”

Here’s how wikipedia defines the term:

False equivalence is a logical fallacy in which two completely opposing arguments appear to be logically equivalent when in fact they are not.

But what if the two perspectives on climate change (that it’s real versus fake) are equal if you use a different criteria than just data (meaning sample size)? What if the story of a record setting blizzard is more convincing to someone that the climate isn’t warming than a graph showing a net warming of winters.

The blizzard might have one great, dramatic, painful anecdote of someone freezing to death in the snow. Such a story might be fairly convincing to many that the climate isn’t warming. The graph is only information.

Everyone should read the extremely simple, extremely powerful, extremely broadly written classic 2009 article by three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Nicholas Kristof of the NY Times. I use it endlessly in my workshops and trainings. He presents this basic property of narrative that it reaches it’s greatest strength with the story of only one person. He cites the age old adage (attributed by some to Stalin) that, “The death of one person is a tragedy, the death of a million is just a statistic.”

FAULTY PROGRAMMING

The bottom line, as I’ve lectured and written on for more than a decade now, is that the brain has faulty programming. Narrative overwhelms the analytical part of the brain. It sucks, but it’s a fact. And it leaves scientists handicapped when it comes to communication. And even further handicapped by the desire to ignore that they have programming faults rather than admit it and work on it.

Here’s the detailed treatment I gave the problem in my recent book, “Narrative Is Everything.”

YES, SCIENTISTS ARE HUMAN, BUT THEY DEFINITELY ARE DIFFERENT WHEN IT COMES TO PERCEIVING NARRATIVE

Scientists actually are different from non-scientists in how they think. That’s what we need to begin with. Remember Jerry Graff’s book title and general template for argumentation? His book is titled They Say, I Say. Let’s use that as our template for where we are so far in our journey through these five broad topics.

“They say” is our first three chapters (business, politics, entertainment). Just about everyone involved in those worlds accepts the importance of the singular narrative. Business people know you want to focus on the one main thing that distinguishes your product from the pack. Politicians know they need a clear singular message. And for the entertainment world, the question of “Whose story is it?” is the basic concession that you need to have one central narrative thread and stick to it if you want to tap into the power of Archplot (classical design) to reach a large audience (meaning the Outer Circle).

In 2012, the bestselling book The One Thing was voted one of the top ten business books of all time on the website Goodreads. It was custom-made for the business world, but it didn’t begin to suggest applying singular thinking to the world of science. Here’s why.

THE FUNDAMENTAL CONUNDRUM: THE SINGULAR NARRATIVE VERSUS GIANT SAMPLE SIZE

Scientists love big numbers—especially when it comes to sample size. As a scientist, you spend your life gathering and analyzing data. There is always this relentless force driving you to obtain larger sample sizes. It gets programmed into your psyche: big number good, small number bad. The worst number of all is one, the “anecdote.”

When you listen to a talk and the speaker says “exactly 40 percent of the moths were white,” you get a squeamish feeling. You think, “please don’t tell me you observed only five moths, and two were white …”

But then the speaker puts up the data and the value mentioned is actually 40.246%. You begin to relax. And then you see the sample size was 1,283,472 moths, and you say to yourself, “Wow. Over one milllllllion moths!”

You feel very, very good just looking at that large number on the screen. At the same time, you retain your dread fear of a sample size of just one. And of course that’s what an anecdote is: a single instance. It’s “n equals one,” in the parlance of scientists.

ANECDOTES: THE BANE OF SCIENCE

Storytellers love the singular narrative, which means they love the anecdote. Take a look at any issue of The New Yorker, and you’ll find at least one article that opens with an anecdote about one person.

In fact, let’s put this to the test right now. I’m opening up the March 18, 2019, issue of The New Yorker, which I just received yesterday. I’m seeing an article called, “The Perfect Paint: Farrow and Ball’s Selective Palette Is Creating a New Kind of Decorating Anxiety.” I’m turning to the article, and I’m reading the first paragraph, which begins with, “When Haley Allman and her husband bought an Edwardian town house … ” And there you have it—it opens with the story of one person, Haley (her husband is just an added detail)—the classic anecdote.

You can find at least one major article in just about every issue of The New Yorker that starts like this. The singular anecdote provides immediate focus and locks in your interest while conveying the basic theme of what’s about to be explored. But to scientists, it’s fundamentally wrong.

I developed an intimate familiarity with this in my science career. For example, one of my marine biological projects involved diving under the ice in Antarctica. The climate there was brutally cold, and for one starfish species we studied, I was only able to find one individual of the species and make one measurement. When it came time to publish a paper about the project, there was discussion over whether I should be allowed to mention that one observation, since it was “just an anecdote.”

The discussion came down to the question of whether the world of science would be better off knowing this one tidbit of unreplicated information, or whether science would be better if no one ever even heard it. It’s a bit like a judge ruling on whether hearsay evidence is admissible in court. We chose to not mention it. (P.S. The only recording of that one measurement was in a notebook that was in my house that burned down, so the world will never know that tiny piece of starfish data, boo hoo.)

This is how scientists are absolutely different from non- scientists. You are trained to be suspect and spurn anecdotes and be suspicious of them. And yet, the brain of the average human loves them—as exemplified in the extreme with the examples from Nicholas Kristof I mentioned in the first chapter about the advertisements of children dying in Africa. That communication was at its most powerful when the sample size of individuals being talked about was one.

So scientists dream of communicating in this somewhat non- human, anecdote-free manner that involves the luxury of running through all 43 points you want to make. When I work with them I can usually convince them that 43 is too much. But when you start to get down to their wanting to tell three stories versus my recommending they yield to Dave Gold’s single Christmas-tree model—that’s where it can get ugly .

They will push back, saying there is no one single story. I will push forward, saying, “Maybe there is, and you just haven’t realized it yet.” They will say three is good enough, I will try to point out there is greater power in the singular narrative and they will start to glare at me as though I am the enemy. I’ve been through it many times.

Scientists are different this way. I know because I used to be one. They yearn for an AAA-accepting world, but the truth is, they are the ones who have produced the technology that has glutted our world with information, resulting in even less tolerance for the AAA form. The world used to be more AAA, but narrative selection has changed the landscape — which will be our major topic for Chapter 6.