Slogans are essential for effective mass messaging, but there seems to be no simple structural rules for creating them. At all. Here’s a first one. It’s “The Therefore Test.” Just say the word THEREFORE before the slogan. Yep, it’s that simple, and will tell you plenty. Jayde Lovell did an interview with me about this last week which just aired on the new Young Turks Network (TYT) digital television channel. You can view it here.

A SLOGAN SHOULD BE A STATEMENT OF CONSEQUENCE

Narrative consists of three main forces — agreement, contradiction, consequence. Guess which force a slogan should embody.

If your slogan consists only of agreement it’s going to be boring. If it conveys only contradiction it will be confusing and unfulfilling. But if it’s a statement of consequence, it’s pushing forward and ideally even conveys the ultimate goal — action.

The ABT Narrative Template (And, But, Therefore) embodies the three forces. So this is yet another application of the ABT tool.

THE “THEREFORE TEST” FOR SLOGANS

This becomes a very simple test for a slogan — just say the word “therefore,” then say the slogan. Try it on some of the best slogans ever. Each one rolls off the tongue after the word of consequence.

THEREFORE … give me liberty or give me death.

THEREFORE … just do it.

THEREFORE … you’re in good hands.

THEREFORE … better dead than red.

THEREFORE … I can feel a Fourex comin’ on

The last one is my favorite from living a few years in northern Australia. The test isn’t the defining criteria for every possible slogan, but seems to work for most.

YOU CAN FEEL THE ABT THAT CAME BEFORE

Really good slogans, like these, seem to almost project backwards as you can feel what the ABT (And, But, Therefore narrative structure) was that brought you to the slogan. Here’s the matching ABTs for the above …

The crown is having its way with us AND there are those who urge caution, BUT we can no longer endure the repression, THEREFORE … give me liberty or give me death.

You may want to hesitate AND it would be easy to not act, BUT life is short, THEREFORE … just do it.

You need reliable insurance AND many companies don’t provide it, BUT Allstate does, THEREFORE … you’re in good hands (with Allstate)

There is disagreement in this country about the threat of communism AND some feel it’s not a danger, BUT we say it threatens our entire existence, THEREFORE … we’re better dead than red.

Fourex is the best beer in Queensland AND you don’t want to drink too much of it, BUT I’m done with work, THEREFORE … I can feel a Fourex comin’ on.

TRUMP SHOWS HOW IT WORKS

(Trump Warning: if you can’t stomach Donald Trump you might want to skip this section) Wanna learn a few things about mass messaging in today’s information-glutted society? You really should set your emotions aside and engage in the clinical analysis of Trump’s communications traits (I’m hesitant to use the word “skills”). I’ve been doing this for 3 years now, including this episode of the podcast, “The Business of Story,” the morning after the election. It proved to be one of their most popular and has produced lots of emails to me from listeners over the past two years.

Look how Trump’s slogan makes sense coming off the word of consequence:

THEREFORE … make America great again.

And now look at how logical the ABT is that precedes it.

America was once a great AND mighty nation, BUT we’ve slipped in the world, THEREFORE … we need to make America great again.

It’s more than three years since Trump announced “Make America Great Again” as his official slogan in July, 2015. He has not changed one word of it from the start. That reflects how much of a bullseye he hit with the narrative structure from the start, showing once again that narrative is everything.

THEREFORE … LET’S LOOK AT CURRENT CAMPAIGN SLOGANS

Now it’s time to put The THEREFORE Test to work by looking at some of the current crop of political candidates and their slogans. Here we go.

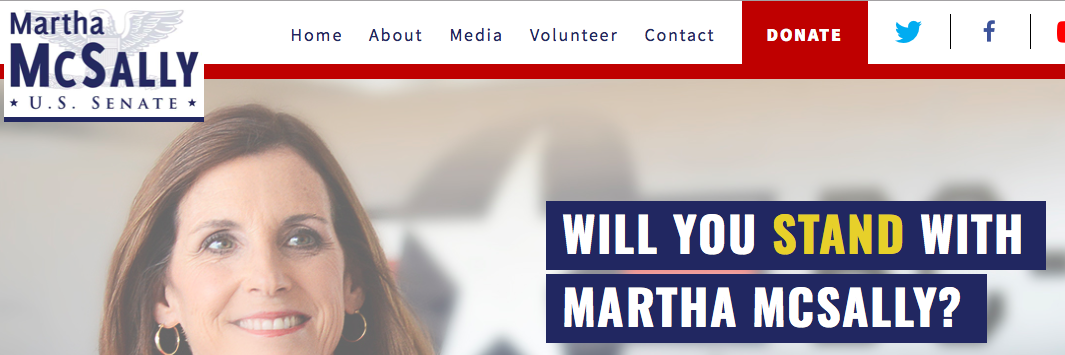

1) ARIZONA: ARIZONA: MCSALLY (REP) VS SINEMA (DEM)

In what may be the most intense race between two women this year, there is the military veteran Martha McSally running against the charismatic activist and current Representative Krysten Sinema. Here are screen grabs of their slogans on their websites.

McSally has the better slogan(s), though neither is very good. She has two slogans. Let’s try them out:

THEREFORE … will you STAND with Martha McSally?

THEREFORE … make no mistake.

Both are firm and confident, reflecting her military background, but both are vague. Is there one specific issue she is STANDING on, and is there one major decision she wants you to make no mistake about? Both are consequential, but kind of empty.

More important — she has two slogans. That’s not good. How many slogans has Trump had? As the bestselling 2012 book, “The One Thing,” will tell you, it’s about … the one thing — meaning “the singular narrative” when it comes to mass communication.

Sinema’s is worse. All she has is a statement — like this:

THEREFORE … an independent voice for Arizona.

It’s not terrible. As a general rule, if you can’t think of something powerful, short and clever then just go with a simple statement of a relevant fact — which is what this is. Not bad, not good.

2) TENNESSEE: BREDESON (DEM) VS BLACKBURN (REP)

The race for Bob Corker’s open senate seat in Tennessee has a businessman, Phil Bredeson, running against Marsha Blackburn, a current Representative.

These are both pretty dull.

THEREFORE … working together to get things done for Tennessee.

THEREFORE … Tennessee values first, Tennessee values always.

Neither of them have much of a ring to them. They are kind of bare minimum, platitude-ish. Yes, we all want to get things done and are for “values.” Neither says much. When in doubt, just make a simple statement like these — doesn’t hurt, doesn’t help much.

3) KANSAS: KELLY (DEM) VS KOBACH (REP)

In the Kansas governor’s race it’s state senator Laura Kelly against current Secretary of State of Kansas, Kris Kobach.

THEREFORE … we are no longer ceding this state. We are determined to take it back.

THEREFORE … time to lead (the conservatives to fix Topeka).

Someone needs to tell the Kelly campaign two sentences is not how you make a slogan. Yes, the statement is clear, but there’s no ring to it — it’s too long — meaning it simply isn’t a slogan. Try putting that on a t-shirt. Not gonna work.

Kobach’s slogan is passable — “time to lead” — but doesn’t say much. The funny part is the second half — to fix Topeka — given that the conservatives under Brownback broke it.

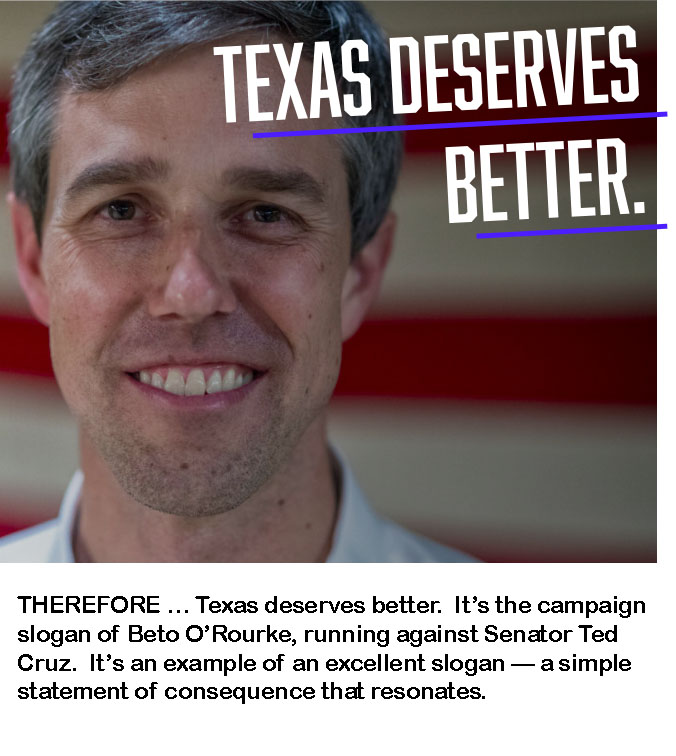

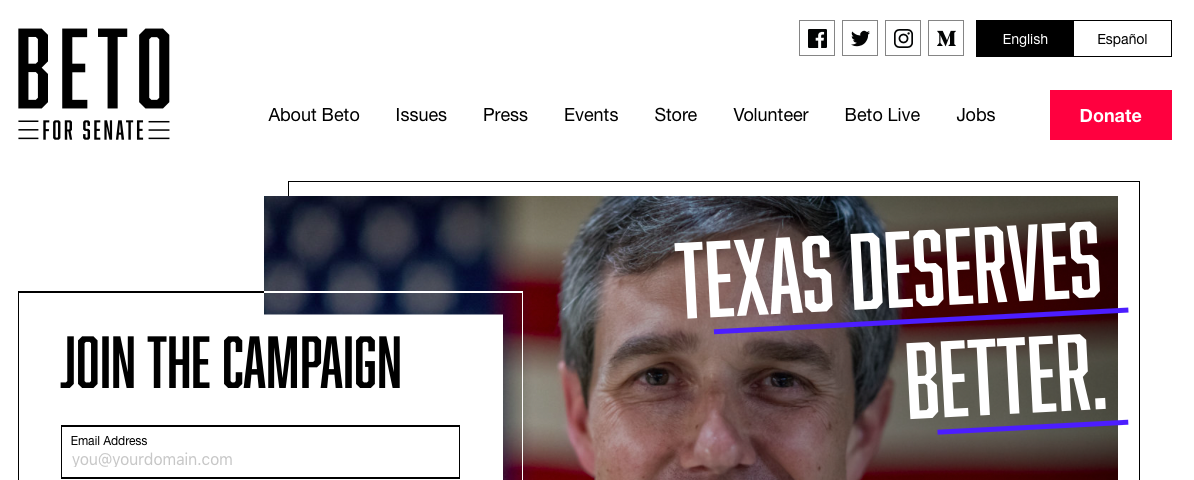

4) TEXAS: O’ROURKE (DEM) VS CRUZ (REP)

Okay, here’s an A-level contest that clearly has A-level talent behind their communications. The upstart challenger Beto O’Rourke is taking on the incumbent Ted Cruz.

THEREFORE … Texas deserves better.

THEREFORE … tough as Texas.

Beto’s slogan is great! It’s the kind of thing you can hear people muttering to themselves all day long — basically “we deserve better than this.” It’s not at all specific, but it’s punchy and rolls perfectly off of THEREFORE. It’s in the realm of “Just Do It.” The only problem he has is that …

Ted’s slogan is equally powerful. It plays off of the longtime campaign of “Don’t Mess With Texas.”

You can feel the ABTs preceding both.

BETO: Texas has had some great politicians and they have done the state well, BUT right now there’s some lousy politicians, THEREFORE Texas deserves better.

TED: Politics can be fun AND produce great things, BUT it can also get really ugly in DC, THEREFORE we need a senator to represent us who is Tough as Texas.

It’s gonna be a fierce next 6 weeks for this election.

5) INTERMISSION: THE SWING LEFT CAMPAIGN

This is my favorite of all the slogans for this fall. It’s Swing Left, the nationwide activist campaign for the Democrats.

THEREFORE … don’t despair. Mobilize

That’s the best ever. Whoever made this slogan up needs to go to work for the Democratic party in general to create a slogan that can go on the black hat I wore in my interview with Jayde. Seriously.

Think about the ABT that sets it up:

Trump won the presidency AND we’ve had some rough times, BUT it’s not going to help anything to give up, THEREFORE don’t despair — MOBILIZE (dammit)!

It’s just about perfect. It has contradiction — going against the urge to despair. It is aspirational — get going and mobilize. And it’s faintly funny. It’s great.

6) NEW YORK: MOLINARO (REP) VS CUOMO (DEM)

Now we go from the best to the worst. Ugh. The hopeless Republican challenger Marc Molinaro is taking on the Andrew Cuomo machine.

Let’s listen to them coming off the THEREFORE.

THEREFORE … let’s believe again.

THEREFORE ………….. together …….. ahead? (um … whut?)

Molinaro doesn’t really seem to have a slogan. His paragraph statement would work better as more of an ABT (“We in NY believe in this AND this, BUT recent folks have messed things up, THEREFORE elect me and let’s believe again.”)

But far more fascinating and borderline nauseating is what’s on Cuomo’s page — “Together Ahead.” Everyone in the Democratic party needs to take a deep breath and realize that slogan represents everything that has got the Democrats into their tailspin of ineptitude that now characterizes the party. It’s a slogan that not only has no ring to it, it’s downright BBB (Bland Beyond Belief).

Where did such a meaningless slogan come from? I can offer a pretty solid guess. I’m gonna bet there are more than one hard core Hillary supporters in his communications team and that they are still believing that her slogan, “Stronger Together” was a good one (it wasn’t — it was terrible). So they are thinking by using the same word “Together” they are resonating with her wonderful campaign. Ugh.

“Together Ahead” is just a terrible slogan. Cuomo is so far ahead it won’t matter, which is kind of a shame — people will associate his huge victory with the slogan, as if one caused the other, but just think about what it says. It’s two narrative directions. Either word by itself would be better. Just make it, “Together!” or make it “Ahead!” It’s a perfect example of “more is less.” Keep it simple, eggheads.

WEAPONIZING THE ABT

That’s probably enough slogans for now. Except one more.

Did you see the brilliant Bigfoot campaign commercial last week for Dean Phillips, running for representative in Minnesota’s 3rd district? I love it to the nth degree. It’s my kind of commercial — way more than MJ Hegar’s “door, door, door” commercial a couple months ago — which was good, but not brilliant like this spot.

Not surprisingly, his campaign has an excellent slogan:

THEREFORE … everyone’s invited.

And the preceding ABT would be:

My opponent claims to represent the district AND thinks he’s a voice for the public BUT the truth is he isn’t, THEREFORE for Dean Phillips campaign, everyone’s invited.

SO WHAT DO YOU WANT FOR A SLOGAN?

Here’s the short checklist I offer up. There’s lots of “experts” on this communication stuff, but few are able to offer up a rational/analytical explanation for their instructions. The ABT makes this possible.

1) CONSEQUENTIAL – that it rolls off of “THEREFORE”

2) SINGULAR – just one slogan

3) CONTRADICTION – implies some element of contradiction to something else

4) ASPIRATIONAL – ideally, is inspiring people to reach for something

5) CONCISE – short and has a ring to it