Communication and acting are one in the same, AND … thinking is the enemy of both. I’ve learned this over the past 25 years from the acting classes, filmmaking and communications work I’ve done since leaving my tenured professorship of biology. It is now the core principle of our Story Circles Narrative Training program. It was difficult for me to absorb in 1994 when (still an academic) I first heard it. To someone with a graduate education it feels alien. But it really is the central conundrum that is like the Observer Effect: How can a thinky person communicate well when thinking ruins the process itself?

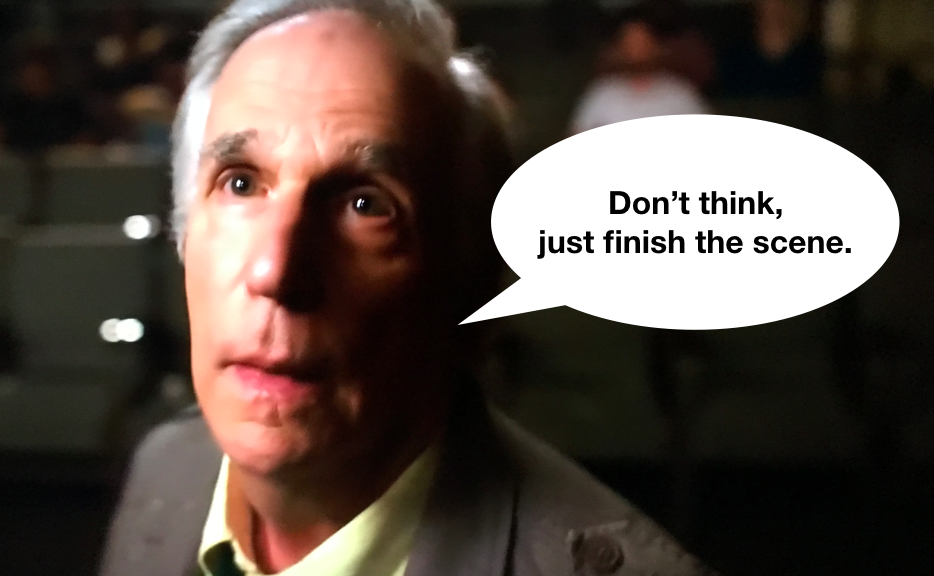

THE FONZ IN ACTION. This was a key moment in the first episode of the acclaimed HBO series, “Barry.” Acting teacher, Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler) manipulates a student to get her into character, then right when her anger is peaking, he tells her to go into the scene she had been performing poorly, and don’t let thinking get in the way. Season Two of “Barry” is starting soon. Can’t wait.

THE CORE PRINCIPLE FOR ACTING/COMMUNICATION: DON’T THINK

The opening paragraph of my first book, “Don’t Be Such A Scientist,” is a string of profanity from my “crazy acting teacher” on the first night of my first acting class in 1994. The source of the tirade was her realization that she had an academic (me) in the class. Academics think, thinking ruins acting, therefore academics must be chased out of an acting class.

Nobody had warned me.

It would take roughly 20 years for me to make sense of what happened that night, but it did eventually make sense. And it makes even more sense when I see the dynamic repeated on a popular TV show.

It occurred last year in the acclaimed HBO series, “Barry.” The persona of my crazy acting teacher (and countless others) is brought to life as Gene Cousineau, an acting teacher played brilliantly by the great Henry Winkler. In the first episode he brings a student to tears of anger. She was performing a scene poorly — failing to show the anger the performance needed. He ignites her emotions, then at just the right moment says to her, “Don’t think, just finish the scene.”

It was the “Don’t think” part that gave me flashbacks to my acting class.

Henry Winkler’s character is so perfect. In Vanity Fair last year he talked about the sources he draws on for the role, with the most obvious being the legendary Stella Adler. Pretty much all acting teachers have at least a little bit of nuttiness to them. But so does human behavior in general.

And that’s why actors, more than anyone else, have a deep understanding of how humans behave — way more than people with PhD’s. The academics can theorize about behavior, but the good actors actually know it so well they can recreate it themselves.

YOU HAVE TO GET “OUT OF YOUR HEAD”

So this ends up being the big challenge. Humans are mostly driven viscerally. Yes, there’s a small percentage who are more cerebral, but they’re not that abundant and most of them turn out to be less logical than they think they are. All you have to do is look at a major academic squabble. I was on an email years ago with a group of professors who suddenly turned on each other over a political issue. An actor friend who read the emails commented, “When eggheads crack …”

Or read my buddy Jerry Graf’s great book, “Clueless in Academe.”

Thinking is humanity’s greatest asset, yet also has a down side. When it comes to science, thinking is essential for half of it (doing research), yet at the same time, is disastrous for the other half (communicating). The first part requires enormous amounts of thinking and seeks perfection as the ultimate goal — i.e. a scientist wants to measure things to the n-th degree.

But communication is the opposite. It needs to be human, alive and visceral. Thinking fouls it up.

The same is true when it comes to training, as we have learned.

“STOP THINKING AND DO THE WORK!”

It’s been 25 years now since my crazy acting class. I’ve forgotten major parts of it. But a couple months ago, a friend reminded me what the crazy acting teacher used to shout at us, night after night — “Stop f-ing thinking and DO THE WORK!”

The cause of her frustration was watching students, who were there to learn from her, fall into the habit of hearing her instructions, THINKING to themselves, “Let’s see, does what she says make sense to me?” then ending up hesitating, doing things wrong, and even criticizing her, even though they had no background in acting.

Her training program was at its core very simple — it just required that everyone do the simple exercises the right way, over and over and over again. Which is exactly the same principle I built our Story Circles Narrative Training on.

And so now, all these years later, I find myself wanting to channel her voice. We work with academics. Some groups — like National Park Service, USDA, USGS, and US Fish and Wildlife Service — do an incredibly good job of exactly what she always asked for — trusting us, listening as close as possible, then doing the simple exercises as best as possible. With time — with repetition — they begin to develop the very “narrative intuition” that is the goal of the training (we’re getting ready to release our first survey of graduates).

But there are some institutions where the participants are not able to get “out of their heads.” They can’t seem to stop themselves from constantly thinking, “Does this make sense — is this the way I would do this — is there a better way to do it that I should recommend to them?”

Those groups are sad to watch. They make a mess out of the training, learning little, then hand us back a stack of critical comments based on how they would do the training — even though they are not good at narrative. It was the same problem that drove the acting teacher crazy. I now feel her pain.

So I guess sometimes I wish I could just bring Gene Cousineau to our training sessions. He would know exactly what to say to them. “Don’t think — just do the work.”

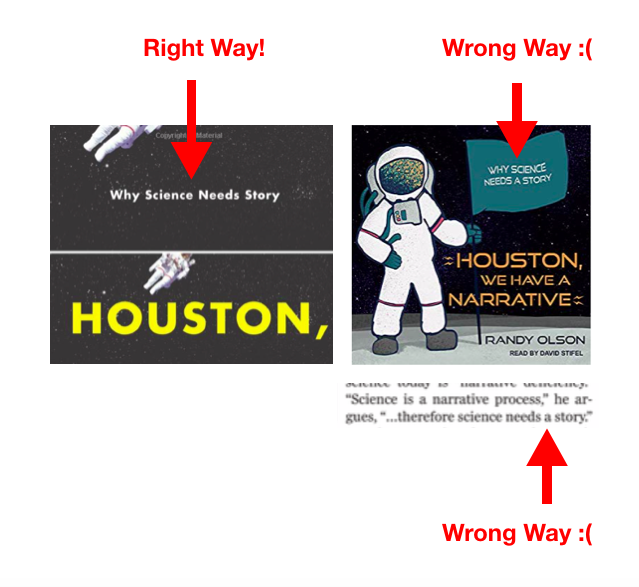

FLASHBACK TO 15 YEARS AGO. This was my one great morning I got to spend working with the wonderful Henry Winkler in the spring of 2003 in the filming of our Ocean Symphony PSA with Jack Black. He was as awesome back then as he is today (also pictured: Madeline Stowe on violin, Michael Hitchcock behind her, Sharon Lawrence on kettle drums, and Mindy “Frau Farbissina” Sterling seated next to her).